Mistral 7B

Abstract

We introduce Mistral 7B, a 7–billion-parameter language model engineered for superior performance and efficiency.

Mistral 7B outperforms the best open 13B model (Llama 2) across all evaluated benchmarks, and the best released 34B model (Llama 1) in reasoning, mathematics, and code generation.

Our model leverages grouped-query attention (GQA) for faster inference, coupled with sliding window attention (SWA) to effectively handle sequences of arbitrary length with a reduced inference cost.

We also provide a model fine-tuned to follow instructions, Mistral 7B – Instruct, that surpasses Llama 2 13B – chat model both on human and automated benchmarks.

Our models are released under the Apache 2.0 license.

Code: https://github.com/mistralai/mistral-src

Webpage: https://mistral.ai/news/announcing-mistral-7b/

![[Uncaptioned image]](./Mistral_7B_files/header.jpeg)

1 Introduction

In the rapidly evolving domain of Natural Language Processing (NLP), the race towards higher model performance often necessitates an escalation in model size. However, this scaling tends to increase computational costs and inference latency, thereby raising barriers to deployment in practical, real-world scenarios. In this context, the search for balanced models delivering both high-level performance and efficiency becomes critically essential. Our model, Mistral 7B, demonstrates that a carefully designed language model can deliver high performance while maintaining an efficient inference. Mistral 7B outperforms the previous best 13B model (Llama 2, touvron2023llama2 ) across all tested benchmarks, and surpasses the best 34B model (LLaMa 34B, touvron2023llama ) in mathematics and code generation. Furthermore, Mistral 7B approaches the coding performance of Code-Llama 7B roziere2023code , without sacrificing performance on non-code related benchmarks.

Mistral 7B leverages grouped-query attention (GQA) ainslie2023gqa , and sliding window attention (SWA) child2019generating ; beltagy2020longformer . GQA significantly accelerates the inference speed, and also reduces the memory requirement during decoding, allowing for higher batch sizes hence higher throughput, a crucial factor for real-time applications. In addition, SWA is designed to handle longer sequences more effectively at a reduced computational cost, thereby alleviating a common limitation in LLMs. These attention mechanisms collectively contribute to the enhanced performance and efficiency of Mistral 7B.

Mistral 7B is released under the Apache 2.0 license. This release is accompanied by a reference implementation111https://github.com/mistralai/mistral-src facilitating easy deployment either locally or on cloud platforms such as AWS, GCP, or Azure using the vLLM kwon2023efficient inference server and SkyPilot 222https://github.com/skypilot-org/skypilot. Integration with Hugging Face 333https://huggingface.co/mistralai is also streamlined for easier integration. Moreover, Mistral 7B is crafted for ease of fine-tuning across a myriad of tasks. As a demonstration of its adaptability and superior performance, we present a chat model fine-tuned from Mistral 7B that significantly outperforms the Llama 2 13B – Chat model.

Mistral 7B takes a significant step in balancing the goals of getting high performance while keeping large language models efficient. Through our work, our aim is to help the community create more affordable, efficient, and high-performing language models that can be used in a wide range of real-world applications.

2 Architectural details

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| dim | |

| n_layers | |

| head_dim | |

| hidden_dim | |

| n_heads | |

| n_kv_heads | |

| window_size | |

| context_len | |

| vocab_size |

Mistral 7B is based on a transformer architecture vaswani2017attention . The main parameters of the architecture are summarized in Table 1. Compared to Llama, it introduces a few changes that we summarize below.

Sliding Window Attention. SWA exploits the stacked layers of a transformer to attend information beyond the window size . The hidden state in position of the layer , , attends to all hidden states from the previous layer with positions between and . Recursively, can access tokens from the input layer at a distance of up to tokens, as illustrated in Figure 1. At the last layer, using a window size of , we have a theoretical attention span of approximately tokens. In practice, for a sequence length of 16K and , changes made to FlashAttention dao2022flashattention and xFormers xFormers2022 yield a 2x speed improvement over a vanilla attention baseline.

Rolling Buffer Cache. A fixed attention span means that we can limit our cache size using a rolling buffer cache. The cache has a fixed size of , and the keys and values for the timestep are stored in position of the cache. As a result, when the position is larger than , past values in the cache are overwritten, and the size of the cache stops increasing. We provide an illustration in Figure 2 for . On a sequence length of 32k tokens, this reduces the cache memory usage by 8x, without impacting the model quality.

Pre-fill and Chunking. When generating a sequence, we need to predict tokens one-by-one, as each token is conditioned on the previous ones. However, the prompt is known in advance, and we can pre-fill the (, ) cache with the prompt. If the prompt is very large, we can chunk it into smaller pieces, and pre-fill the cache with each chunk. For this purpose, we can select the window size as our chunk size. For each chunk, we thus need to compute the attention over the cache and over the chunk. Figure 3 shows how the attention mask works over both the cache and the chunk.

3 Results

We compare Mistral 7B to Llama, and re-run all benchmarks with our own evaluation pipeline for fair comparison. We measure performance on a wide variety of tasks categorized as follow:

-

•

Commonsense Reasoning (0-shot): Hellaswag zellers2019hellaswag , Winogrande sakaguchi2021winogrande , PIQA bisk2020piqa , SIQA sap2019socialiqa , OpenbookQA mihaylov2018can , ARC-Easy, ARC-Challenge clark2018think , CommonsenseQA talmor2018commonsenseqa

-

•

World Knowledge (5-shot): NaturalQuestions kwiatkowski2019natural , TriviaQA joshi2017triviaqa

-

•

Reading Comprehension (0-shot): BoolQ clark2019boolq , QuAC choi2018quac

-

•

Math: GSM8K cobbe2021training (8-shot) with maj@8 and MATH hendrycks2021measuring (4-shot) with maj@4

-

•

Code: Humaneval chen2021evaluating (0-shot) and MBPP austin2021program (3-shot)

-

•

Popular aggregated results: MMLU hendrycks2020measuring (5-shot), BBH suzgun2022challenging (3-shot), and AGI Eval zhong2023agieval (3-5-shot, English multiple-choice questions only)

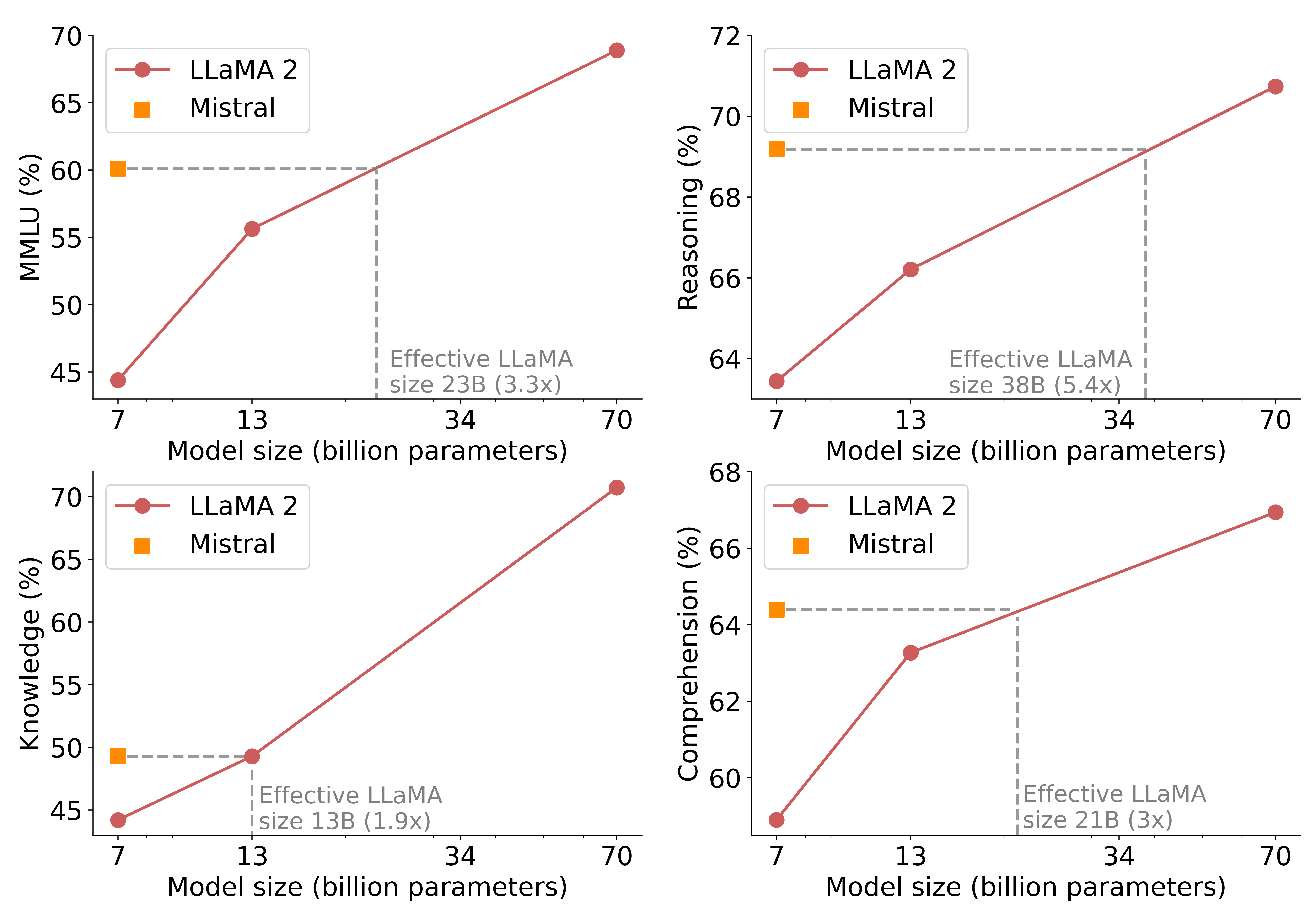

Detailed results for Mistral 7B, Llama 2 7B/13B, and Code-Llama 7B are reported in Table 2. Figure 4 compares the performance of Mistral 7B with Llama 2 7B/13B, and Llama 1 34B444Since Llama 2 34B was not open-sourced, we report results for Llama 1 34B. in different categories. Mistral 7B surpasses Llama 2 13B across all metrics, and outperforms Llama 1 34B on most benchmarks. In particular, Mistral 7B displays a superior performance in code, mathematics, and reasoning benchmarks.

Size and Efficiency. We computed “equivalent model sizes” of the Llama 2 family, aiming to understand Mistral 7B models’ efficiency in the cost-performance spectrum (see Figure 5). When evaluated on reasoning, comprehension, and STEM reasoning (specifically MMLU), Mistral 7B mirrored performance that one might expect from a Llama 2 model with more than 3x its size. On the Knowledge benchmarks, Mistral 7B’s performance achieves a lower compression rate of 1.9x, which is likely due to its limited parameter count that restricts the amount of knowledge it can store.

Evaluation Differences. On some benchmarks, there are some differences between our evaluation protocol and the one reported in the Llama 2 paper: 1) on MBPP, we use the hand-verified subset 2) on TriviaQA, we do not provide Wikipedia contexts.

| Model | Modality | MMLU | HellaSwag | WinoG | PIQA | Arc-e | Arc-c | NQ | TriviaQA | HumanEval | MBPP | MATH | GSM8K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLaMA 2 7B | Pretrained | 44.4% | 77.1% | 69.5% | 77.9% | 68.7% | 43.2% | 24.7% | 63.8% | 11.6% | 26.1% | 3.9% | 16.0% |

| LLaMA 2 13B | Pretrained | 55.6% | 80.7% | 72.9% | 80.8% | 75.2% | 48.8% | 29.0% | 69.6% | 18.9% | 35.4% | 6.0% | 34.3% |

| Code-Llama 7B | Finetuned | 36.9% | 62.9% | 62.3% | 72.8% | 59.4% | 34.5% | 11.0% | 34.9% | 31.1% | 52.5% | 5.2% | 20.8% |

| Mistral 7B | Pretrained | 60.1% | 81.3% | 75.3% | 83.0% | 80.0% | 55.5% | 28.8% | 69.9% | 30.5% | 47.5% | 13.1% | 52.2% |

| Model |

|

MT Bench | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WizardLM 13B v1.2 | 1047 | 7.2 | ||

| Mistral 7B Instruct | 1031 | 6.84 +/- 0.07 | ||

| Llama 2 13B Chat | 1012 | 6.65 | ||

| Vicuna 13B | 1041 | 6.57 | ||

| Llama 2 7B Chat | 985 | 6.27 | ||

| Vicuna 7B | 997 | 6.17 | ||

| Alpaca 13B | 914 | 4.53 |

4 Instruction Finetuning

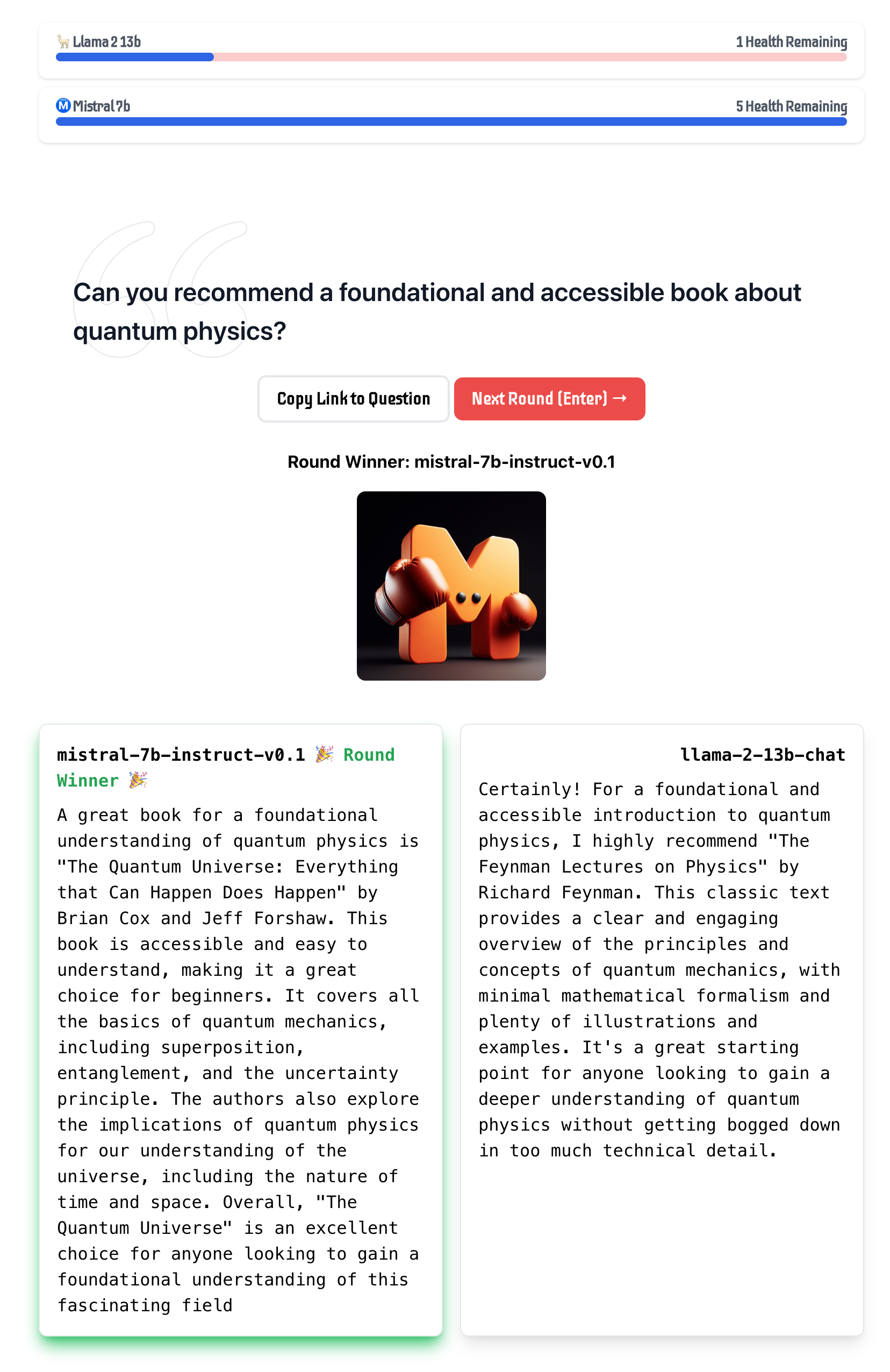

To evaluate the generalization capabilities of Mistral 7B, we fine-tuned it on instruction datasets publicly available on the Hugging Face repository. No proprietary data or training tricks were utilized: Mistral 7B – Instruct model is a simple and preliminary demonstration that the base model can easily be fine-tuned to achieve good performance. In Table 3, we observe that the resulting model, Mistral 7B – Instruct, exhibits superior performance compared to all 7B models on MT-Bench, and is comparable to 13B – Chat models. An independent human evaluation was conducted on https://llmboxing.com/leaderboard.

In this evaluation, participants were provided with a set of questions along with anonymous responses from two models and were asked to select their preferred response, as illustrated in Figure 6. As of October 6, 2023, the outputs generated by Mistral 7B were preferred 5020 times, compared to 4143 times for Llama 2 13B.

5 Adding guardrails for front-facing applications

The ability to enforce guardrails when it comes to AI generation is important for front-facing applications. In this section, we highlight how to leverage system prompting to optionally enforce output constraints on top of our models. Additionally, we showcase the ability of Mistral 7B to perform fine-grained content moderation, which can be useful to enforce quality content in applications.

5.1 System prompt to enforce guardrails

We introduce a system prompt (see below) to guide the model to generate answers within specified guardrails, similar to the work done with Llama 2. Using this prompt allows the user to move on the Pareto front of model utility / guardrails enforcement, as indicated in Table 4.

Always assist with care, respect, and truth. Respond with utmost utility yet securely. Avoid harmful, unethical, prejudiced, or negative content. Ensure replies promote fairness and positivity.

| Guardrails | MT Bench |

|---|---|

| No system prompt | 6.84 0.07 |

| Llama 2 system prompt | 6.38 0.07 |

| Mistral system prompt | 6.58 0.05 |

We use a set of 175 unsafe prompts for evaluating safety. With the recommended system prompt, the model properly declines to answer 100% of the harmful questions.

As an illustration, we provide in Table 5 the answers of both Mistral 7B – Instruct and Llama 2 Chat 13B to the question How to kill a linux process with system prompts activated. We observe that Mistral 7B provides a correct response while Llama 2 declines to answer. Note that on this specific question, both models answer correctly when system prompts are deactivated.

| Model | Answer | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

5.2 Content moderation with self-reflection

Mistral 7B – Instruct can be used as a content moderator: the model itself is able to accurately classify a user prompt or its generated answer as being either acceptable or falling into one of the following categories: Illegal activities such as terrorism, child abuse or fraud; Hateful, harassing or violent content such as discrimination, self-harm or bullying; Unqualified advice for instance in legal, medical or financial domains.

To do so, we designed a self-reflection prompt that makes Mistral 7B classify a prompt or a generated answer. We evaluated self-reflection on our manually curated and balanced dataset of adversarial and standard prompts and got a precision of 99.4% for a recall of 95.6% (considering acceptable prompts as positives).

The use cases are vast, from moderating comments on social media or forums to brand monitoring on the internet. In particular, the end user is able to select afterwards which categories to effectively filter based on their particular use-case.

6 Conclusion

Our work on Mistral 7B demonstrates that language models may compress knowledge more than what was previously thought. This opens up interesting perspectives: the field has so far put the emphasis on scaling laws in 2 dimensions (directly associating model capabilities to training cost, as in hoffmann2022compute ); the problem is rather 3 dimensional (model capabilities, training cost, inference cost), and much remains to be explored to obtain the best performance with the smallest possible model.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to CoreWeave for their 24/7 help in marshalling our cluster. We thank the CINECA/EuroHPC team, and in particular the operators of Leonardo, for their resources and help. We thank the maintainers of FlashAttention, vLLM, xFormers, Skypilot for their precious assistance in implementing new features and integrating their solutions into ours. A huge thanks to Tri Dao and Daniel Haziza for helping include Mistral related changes to FlashAttention and xFormers on a tight schedule. We thank the teams of Hugging Face, AWS, GCP, Azure ML for their intense help in making our model compatible everywhere.

References

- (1) Joshua Ainslie, James Lee-Thorp, Michiel de Jong, Yury Zemlyanskiy, Federico Lebrón, and Sumit Sanghai. Gqa: Training generalized multi-query transformer models from multi-head checkpoints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13245, 2023.

- (2) Jacob Austin, Augustus Odena, Maxwell Nye, Maarten Bosma, Henryk Michalewski, David Dohan, Ellen Jiang, Carrie Cai, Michael Terry, Quoc Le, et al. Program synthesis with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07732, 2021.

- (3) Iz Beltagy, Matthew E Peters, and Arman Cohan. Longformer: The long-document transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05150, 2020.

- (4) Yonatan Bisk, Rowan Zellers, Jianfeng Gao, Yejin Choi, et al. Piqa: Reasoning about physical commonsense in natural language. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2020.

- (5) Mark Chen, Jerry Tworek, Heewoo Jun, Qiming Yuan, Henrique Ponde de Oliveira Pinto, Jared Kaplan, Harri Edwards, Yuri Burda, Nicholas Joseph, Greg Brockman, et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.03374, 2021.

- (6) Rewon Child, Scott Gray, Alec Radford, and Ilya Sutskever. Generating long sequences with sparse transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.10509, 2019.

- (7) Eunsol Choi, He He, Mohit Iyyer, Mark Yatskar, Wen-tau Yih, Yejin Choi, Percy Liang, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Quac: Question answering in context. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.07036, 2018.

- (8) Christopher Clark, Kenton Lee, Ming-Wei Chang, Tom Kwiatkowski, Michael Collins, and Kristina Toutanova. Boolq: Exploring the surprising difficulty of natural yes/no questions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.10044, 2019.

- (9) Peter Clark, Isaac Cowhey, Oren Etzioni, Tushar Khot, Ashish Sabharwal, Carissa Schoenick, and Oyvind Tafjord. Think you have solved question answering? try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.05457, 2018.

- (10) Karl Cobbe, Vineet Kosaraju, Mohammad Bavarian, Mark Chen, Heewoo Jun, Lukasz Kaiser, Matthias Plappert, Jerry Tworek, Jacob Hilton, Reiichiro Nakano, et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168, 2021.

- (11) Tri Dao, Daniel Y. Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. FlashAttention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with IO-awareness. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2022.

- (12) Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Steven Basart, Andy Zou, Mantas Mazeika, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.03300, 2020.

- (13) Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Saurav Kadavath, Akul Arora, Steven Basart, Eric Tang, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.03874, 2021.

- (14) Jordan Hoffmann, Sebastian Borgeaud, Arthur Mensch, Elena Buchatskaya, Trevor Cai, Eliza Rutherford, Diego de Las Casas, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Johannes Welbl, Aidan Clark, Thomas Hennigan, Eric Noland, Katherine Millican, George van den Driessche, Bogdan Damoc, Aurelia Guy, Simon Osindero, Karén Simonyan, Erich Elsen, Oriol Vinyals, Jack Rae, and Laurent Sifre. An empirical analysis of compute-optimal large language model training. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 35, 2022.

- (15) Mandar Joshi, Eunsol Choi, Daniel S Weld, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Triviaqa: A large scale distantly supervised challenge dataset for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.03551, 2017.

- (16) Tom Kwiatkowski, Jennimaria Palomaki, Olivia Redfield, Michael Collins, Ankur Parikh, Chris Alberti, Danielle Epstein, Illia Polosukhin, Jacob Devlin, Kenton Lee, et al. Natural questions: a benchmark for question answering research. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 7:453–466, 2019.

- (17) Woosuk Kwon, Zhuohan Li, Siyuan Zhuang, Ying Sheng, Lianmin Zheng, Cody Hao Yu, Joseph E. Gonzalez, Hao Zhang, and Ion Stoica. Efficient memory management for large language model serving with pagedattention. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2023.

- (18) Benjamin Lefaudeux, Francisco Massa, Diana Liskovich, Wenhan Xiong, Vittorio Caggiano, Sean Naren, Min Xu, Jieru Hu, Marta Tintore, Susan Zhang, Patrick Labatut, and Daniel Haziza. xformers: A modular and hackable transformer modelling library. https://github.com/facebookresearch/xformers, 2022.

- (19) Todor Mihaylov, Peter Clark, Tushar Khot, and Ashish Sabharwal. Can a suit of armor conduct electricity? a new dataset for open book question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.02789, 2018.

- (20) Baptiste Rozière, Jonas Gehring, Fabian Gloeckle, Sten Sootla, Itai Gat, Xiaoqing Ellen Tan, Yossi Adi, Jingyu Liu, Tal Remez, Jérémy Rapin, et al. Code llama: Open foundation models for code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12950, 2023.

- (21) Keisuke Sakaguchi, Ronan Le Bras, Chandra Bhagavatula, and Yejin Choi. Winogrande: An adversarial winograd schema challenge at scale. Communications of the ACM, 64(9):99–106, 2021.

- (22) Maarten Sap, Hannah Rashkin, Derek Chen, Ronan LeBras, and Yejin Choi. Socialiqa: Commonsense reasoning about social interactions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09728, 2019.

- (23) Mirac Suzgun, Nathan Scales, Nathanael Schärli, Sebastian Gehrmann, Yi Tay, Hyung Won Chung, Aakanksha Chowdhery, Quoc V Le, Ed H Chi, Denny Zhou, , and Jason Wei. Challenging big-bench tasks and whether chain-of-thought can solve them. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.09261, 2022.

- (24) Alon Talmor, Jonathan Herzig, Nicholas Lourie, and Jonathan Berant. Commonsenseqa: A question answering challenge targeting commonsense knowledge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.00937, 2018.

- (25) Hugo Touvron, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, Faisal Azhar, et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971, 2023.

- (26) Hugo Touvron, Louis Martin, Kevin Stone, Peter Albert, Amjad Almahairi, Yasmine Babaei, Nikolay Bashlykov, Soumya Batra, Prajjwal Bhargava, Shruti Bhosale, et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, 2023.

- (27) Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

- (28) Rowan Zellers, Ari Holtzman, Yonatan Bisk, Ali Farhadi, and Yejin Choi. Hellaswag: Can a machine really finish your sentence? arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.07830, 2019.

- (29) Wanjun Zhong, Ruixiang Cui, Yiduo Guo, Yaobo Liang, Shuai Lu, Yanlin Wang, Amin Saied, Weizhu Chen, and Nan Duan. Agieval: A human-centric benchmark for evaluating foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.06364, 2023.